BEN CHACKO recommends a handy pamphlet that demonstrates how US opposition to Maduro has systematically distorted our perception of the country and the continuity of its revolution

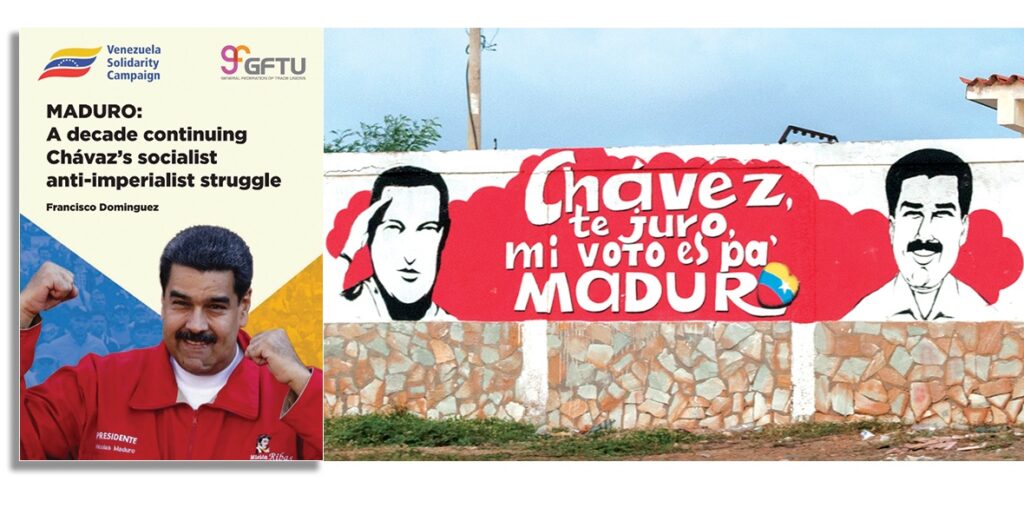

Maduro: A decade Continuing Chavez’s Socialist Anti-imperialist Struggle

Francisco Dominguez, GFTU, £2

THIS pamphlet published by the General Federation of Trade Unions is a handy overview of Venezuela’s last decade.

When Hugo Chavez, the dynamic founder of the Bolivarian Revolution, died in 2013, ruling-class circles in the United States believed Venezuela’s socialist experiment would quickly unravel.

Venezuela Solidarity Campaign secretary Francisco Dominguez shows how wrong they were.

Some on the soft left, in a familiar trajectory, dropped support for Venezuela when things got difficult, arguing that Chavez’s revolution had degenerated into a dictatorship under Nicolas Maduro.

More recently, controversy has emerged over criticisms by the Communist Party of Venezuela (PCV), which accuses the Maduro government of rapprochement with imperialism.

But Dominguez’s study makes a convincing case for the continuity of the Venezuelan revolution.

The US certainly never let up in its hostility, and chapter 2 takes us through the repeated attempts to remove Chavez from power from 1999, most dramatically the April 2002 coup in which the president was actually kidnapped before being freed by a huge mobilisation of ordinary people.

If US officials opined after Chavez’s death that Maduro would rapidly fall from power they didn’t intend to watch and wait.

Perceived weakness would be met with a ferociously intensified economic and political war.

Barack Obama ludicrously declared Venezuela “an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security of the United States” in 2015.

Venezuela was subjected to an increasingly harsh sanctions regime with horrific consequences. Its assets abroad were frozen or stolen — famously 31 tons of gold are still held in the Bank of England. “Banks the world over froze virtually all Venezuelan accounts … oil-related spare parts and refining chemicals were completely blocked, making output collapse.”

Venezuela lost $232 billion in oil revenues; sanctions applied to medicines cost tens of thousands of lives.

A chilling example of the human impact of sanctions is given: in 2019 a Portuguese bank blocked Venezuela’s payment for bone marrow transplants for 26 severely ill citizens at an Italian clinic. Five children died awaiting treatment.

Sanctions were combined with the Venezuelan opposition’s regular recourse to violent uprisings, which lasted months at a time in 2014, 2017 and 2019.

Hundreds of people were killed in these “guarimbas,” with opponents of the government attacking public facilities such as health centres as well as pedestrians, often identifying anyone with dark skin in this racially divided country as a “Chavista”: a parking attendant with no political allegiance, Oscar Figuera, was covered in petrol and burnt to death on such an identification.

The regime change campaign reached its nadir with the US recognition of the unelected Juan Guaido as Venezuela’s president in 2019. But this farce too ended in failure.

Dominguez quotes media reports extensively, providing a useful lesson. Far-right street mobilisations torching buses and lynching black people were presented across Western media as pro-democracy demonstrations (a similarly misleading narrative has been spun about riots in Hong Kong).

The systematic shaping of media reportage reminds me of a Venezuelan photographer I once met, who showed me a portfolio of hundreds of photos of pro- and anti-government demonstrations in the country he had taken in 2019 — and said there was no market for any of the pro-government ones.

Dominguez answers criticisms of economic compromises portrayed by some critics as a sell-out of the revolution. Above all, he supplies evidence that Venezuela’s position has not changed in the eyes of its enemies: the US has consistently regarded it as a threat to be crushed through the Chavez and Maduro presidencies.

But whether or not left critiques of Maduro are justified, the PCV’s accusations that the PSUV seeks to suppress and now replace it with a friendlier duplicate need answering, and it would be useful to see this issue addressed.

Despite its brevity, this booklet covers Venezuela’s experience from multiple angles.

The positives are not just its survival but a new period of strong growth, and a revolutionary democracy bolstered by “tens of thousands of grassroots committees and organisations,” one now taking a leading role in a new wave of left-wing movements across Latin America.

A useful guide for socialists and solidarity campaigners.

This article originally appeared in The Morning Star