By Tim Young, activist with the Venezuela Solidarity Campaign

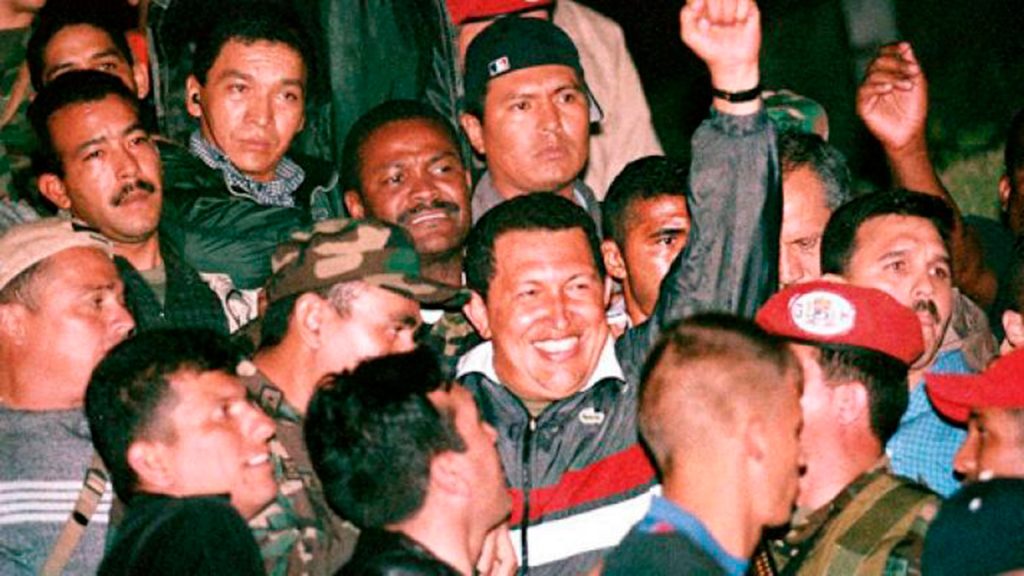

Twenty years ago in Venezuela a right-wing military coup backed by the US briefly overthrew President Hugo Chávez before loyal armed forces units and a mass uprising by Caracas’s barrios returned Chávez to the presidency.

Undeterred, the right-wing opposition then launched a three-month sabotage of the oil industry to try to strangle the economy and force Chávez to resign, but again this was defeated by popular mobilisations.

From then until his untimely death in 2013, Chávez continued to carry out bold programmes to democratise the country and use its oil resources to deliver wide-ranging social and economic improvements, revolutionising a country where previously up to 7 in 10 people had lived in poverty.

But Venezuela’s powerful elites were still unreconciled to these momentous changes which inspired not only ordinary Venezuelans but also progressives across the world hungry for radical reform. The US also continued to view with alarm both Venezuela’s internal transformations and its promotion of a unified Latin America, free from the interference of foreign powers.

The following decade has seen an acceleration in US hostility to Venezuela as its expectations of the demise of Chávez’s Bolivarian Revolution failed to materialise, with President Maduro, Chávez’s preferred successor, winning the presidency in 2013 and again 2018.

US sanctions against Venezuela have been a key element in its strategy to pursue ‘regime change’ and gain control of the world’s largest oil reserves.

First empowered by President Obama’s Executive Order in 2015 declaring Venezuela a threat to US national security, the sanctions – coercive measures illegal under international law – were ratcheted up under President Trump to become a blockade virtually indistinguishable from that imposed on Cuba.

The effects have been similarly far-reaching, with the Washington-based Centre for Economic and Policy Research calculating that US sanctions led to more than 40,000 deaths in 2017-18 alone. When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, sanctions severely restricted Venezuela’s ability to buy medicines and equipment.

US “aid programmes” also supported the right-wing opposition, which in 2014 and 2017 engaged in prolonged and violent street demonstrations and attacks on government supporters and public facilities, without success.

Trump extended this support still further by recognising right-wing opposition leader Juan Guaidό when he declared himself “interim president” in January 2019 and called on supporters to take to the streets to overthrow Maduro – again with no success.

The US urged other countries to recognise Guaidό, while funnelling millions of US dollars’ worth of confiscated Venezuelan assets to him to fund an alternative government.

But Guaidό’s record as “interim president” has been a catalogue of failures, including two failed coups, corruption and links to Colombian drug traffickers. Venezuela’s opposition has fragmented, with more moderate elements engaging in dialogue with the Maduro government and taking part in elections.

Following his election, President Biden has stuck with Trump’s policy for over a year – until the war in Ukraine and the US ban on imports of Russian oil created a domestic energy crisis, with substantial hikes in gasoline and diesel prices.

In early March, the US initiated bilateral talks with the Venezuelan government, the first to take place since President Maduro broke off diplomatic relations in protest against Trump’s recognition of Guaidó.

President Maduro has responded seriously, freeing a Venezuelan-American oil executive imprisoned on corruption charges and a Cuban-American detained for smuggling a drone into the country from Colombia.

He has also committed to restarting talks with the Venezuelan opposition, suspended in response to the US’s illegal removal of Venezuelan diplomat Alex Saab from Cabo Verde to stand trial in the US for so-called ‘sanctions-breaking’.

The renewed dialogue would not only be with the more moderate opposition parties already involved in talks but also, Maduro has offered, with the extreme right-wing parties.

This move may further accelerate divisions and dissent in the opposition, where, for example, approximately a hundred members of the Voluntad Popular –Juan Guaidó’s party when an elected Assembly member – recently quit publicly over a lack of internal democracy.

Guaidό, who was entirely sidelined by the US talks initiative, responded angrily by calling for more sanctions against Venezuela. Opposition to Biden’s opening moves to access Venezuelan oil has also come from long-standing critic Senator Rubio and the right-wing Cuban-Venezuelan constituency in Florida, as well externally from Colombia, El Salvador and Canada.

But some form of accommodation with Venezuela may be inevitable for Biden if other oil producers such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE refuse to assist the US without guarantees of help with their own agendas.

He has already been lobbied by US oil company Chevron for a sanctions waiver to enable it to have more operating control at the four joint ventures it has with PDVSA, Venezuela’s state oil company. Chevron hopes to start moving Venezuelan oil to its refineries before the contractual cut-off date of April 22 for Russian oil imports to the US.

But a minor shift in US sanctions policy, however welcome, would only be a partial victory. We must show our solidarity with Venezuela by redoubling our calls for the entire blockade to be lifted, for Venezuelan assets to be returned to the elected government and for dialogue to take place.

- Register for the Venezuela Solidarity Campaign’s event, 20 years since the coup against Hugo Chavez – Tariq Ali & special guests, on Thursday 28th April 7.30pm, here.

- Sign the petition against illegal sanctions here.

- Sign the petition against the Bank of England’s withholding of Venezuela’s gold resources here .

- Join the Venezuela Solidarity Campaign here.

- Follow VSC on Facebook and Twitter.